How the Brain Creates a Timeline of the Past

It began about a decade ago at Syracuse University, with a set of equations scrawled on a blackboard. Marc Howard, a cognitive neuroscientist now at Boston University, and Karthik Shankar, who was then one of his postdoctoral students, wanted to figure out a mathematical model of time processing: a neurologically computable function for representing the past, like a mental canvas onto which the brain could paint memories and perceptions. “Think about how the retina acts as a display that provides all kinds of visual information,” Howard said. “That’s what time is, for memory. And we want our theory to explain how that display works.”

But it’s fairly straightforward to represent a tableau of visual information, like light intensity or brightness, as functions of certain variables, like wavelength, because dedicated receptors in our eyes directly measure those qualities in what we see. The brain has no such receptors for time. “Color or shape perception, that’s much more obvious,” said Masamichi Hayashi, a cognitive neuroscientist at Osaka University in Japan. “But time is such an elusive property.” To encode that, the brain has to do something less direct.

Pinpointing what that looked like at the level of neurons became Howard and Shankar’s goal. Their only hunch going into the project, Howard said, was his “aesthetic sense that there should be a small number of simple, beautiful rules.”

They came up with equations to describe how the brain might in theory encode time indirectly. In their scheme, as sensory neurons fire in response to an unfolding event, the brain maps the temporal component of that activity to some intermediate representation of the experience — a Laplace transform, in mathematical terms. That representation allows the brain to preserve information about the event as a function of some variable it can encode rather than as a function of time (which it can’t). The brain can then map the intermediate representation back into other activity for a temporal experience — an inverse Laplace transform — to reconstruct a compressed record of what happened when.

Just a few months after Howard and Shankar started to flesh out their theory, other scientists independently uncovered neurons, dubbed “time cells,” that were “as close as we can possibly get to having that explicit record of the past,” Howard said. These cells were each tuned to certain points in a span of time, with some firing, say, one second after a stimulus and others after five seconds, essentially bridging time gaps between experiences. Scientists could look at the cells’ activity and determine when a stimulus had been presented, based on which cells had fired. This was the inverse-Laplace-transform part of the researchers’ framework, the approximation of the function of past time. “I thought, oh my god, this stuff on the blackboard, this could be the real thing,” Howard said.

“It was then I knew the brain was going to cooperate,” he added.

Invigorated by empirical support for their theory, he and his colleagues have been working on a broader framework, which they hope to use to unify the brain’s wildly different types of memory, and more: If their equations are implemented by neurons, they could be used to describe not just the encoding of time but also a slew of other properties — even thought itself.

But that’s a big if. Since the discovery of time cells in 2008, the researchers had seen detailed, confirming evidence of only half of the mathematics involved. The other half — the intermediate representation of time — remained entirely theoretical.

Until last summer.

Orderings and Timestamps

In 2007, a couple of years before Howard and Shankar started tossing around ideas for their framework, Albert Tsao (now a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University) was an undergraduate student doing an internship at the Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience in Norway. He spent the summer in the lab of May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser, who had recently discovered grid cells — the neurons responsible for spatial navigation — in a brain area called the medial entorhinal cortex. Tsao wondered what its sister structure, the lateral entorhinal cortex, might be doing. Both regions provide major input to the hippocampus, which generates our “episodic” memories of experiences that occur at a particular time in a particular place. If the medial entorhinal cortex was responsible for representing the latter, Tsao reasoned, then maybe the lateral entorhinal cortex harbored a signal of time.

The kind of memory-linked time Tsao wanted to think about is deeply rooted in psychology. For us, time is a sequence of events, a measure of gradually changing content. That explains why we remember recent events better than ones from long ago, and why when a certain memory comes to mind, we tend to recall events that occurred around the same time. But how did that add up to an ordered temporal history, and what neural mechanism enabled it?

Tsao didn’t find anything at first. Even pinning down how to approach the problem was tricky because, technically, everything has some temporal quality to it. He examined the neural activity in the lateral entorhinal cortex of rats as they foraged for food in an enclosure, but he couldn’t make heads or tails of what the data showed. No distinctive time signal seemed to emerge.

Tsao tabled the work, returned to school and for years left the data alone. Later, as a graduate student in the Moser lab, he decided to revisit it, this time trying a statistical analysis of cortical neurons at a population level. That’s when he saw it: a firing pattern that, to him, looked a lot like time.

He, the Mosers and their colleagues set up experiments to test this connection further. In one series of trials, a rat was placed in a box, where it was free to roam and forage for food. The researchers recorded neural activity from the lateral entorhinal cortex and nearby brain regions. After a few minutes, they took the rat out of the box and allowed it to rest, then put it back in. They did this 12 times over about an hour and a half, alternating the colors of the walls (which could be black or white) between trials.

What looked like time-related neural behavior arose mainly in the lateral entorhinal cortex. The firing rates of those neurons abruptly spiked when the rat entered the box. As the seconds and then minutes passed, the activity of the neurons decreased at varying rates. That activity ramped up again at the start of the next trial, when the rat reentered the box. Meanwhile, in some cells, activity declined not only during each trial but throughout the entire experiment; in other cells, it increased throughout.

Based on the combination of these patterns, the researchers — and presumably the rats — could tell the different trials apart (tracing the signals back to certain sessions in the box, as if they were timestamps) and arrange them in order. Hundreds of neurons seemed to be working together to keep track of the order of the trials, and the length of each one.

“You get activity patterns that are not simply bridging delays to hold on to information but are parsing the episodic structure of experiences,” said Matthew Shapiro, a neuroscientist at Albany Medical College in New York who was not involved in the study.

The rats seemed to be using these “events” — changes in context — to get a sense of how much time had gone by. The researchers suspected that the signal might therefore look very different when the experiences weren’t so clearly divided into separate episodes. So they had rats run around a figure-eight track in a series of trials, sometimes in one direction and sometimes the other. During this repetitive task, the lateral entorhinal cortex’s time signals overlapped, likely indicating that the rats couldn’t distinguish one trial from another: They blended together in time. The neurons did, however, seem to be tracking the passage of time within single laps, where enough change occurred from one moment to the next.

Tsao and his colleagues were excited because, they posited, they had begun to tease out a mechanism behind subjective time in the brain, one that allowed memories to be distinctly tagged. “It shows how our perception of time is so elastic,” Shapiro said. “A second can last forever. Days can vanish. It’s this coding by parsing episodes that, to me, makes a very neat explanation for the way we see time. We’re processing things that happen in sequences, and what happens in those sequences can determine the subjective estimate for how much time passes.” The researchers now want to learn just how that happens.

Lucy Reading-Ikkanda/Quanta Magazine

Howard’s mathematics could help with that. When he heard about Tsao’s results, which were presented at a conference in 2017 and published in Nature last August, he was ecstatic: The different rates of decay Tsao had observed in the neural activity were exactly what his theory had predicted should happen in the brain’s intermediate representation of experience. “It looked like a Laplace transform of time,” Howard said — the piece of his and Shankar’s model that had been missing from empirical work.

“It was sort of weird,” Howard said. “We had these equations up on the board for the Laplace transform and the inverse around the same time people were discovering time cells. So we spent the last 10 years seeing the inverse, but we hadn’t seen the actual transform. … Now we’ve got it. I’m pretty stoked.”

“It was exciting,” said Kareem Zaghloul, a neurosurgeon and researcher at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland, “because the data they showed was very consistent with [Howard’s] ideas.” (In work published last month, Zaghloul and his team showed how changes in neural states in the human temporal lobe linked directly to people’s performance on a memory task.)

“There was a nonzero probability that all the work my colleagues and students and I had done was just imaginary. That it was about some set of equations that didn’t exist anywhere in the brain or in the world,” Howard added. “Seeing it there, in the data from someone else’s lab — that was a good day.”

Building Timelines of Past and Future

If Howard’s model is true, then it tells us how we create and maintain a timeline of the past — what he describes as a “trailing comet’s tail” that extends behind us as we go about our lives, getting blurrier and more compressed as it recedes into the past. That timeline could be of use not just to episodic memory in the hippocampus, but to working memory in the prefrontal cortex and conditioning responses in the striatum. These “can be understood as different operations working on the same form of temporal history,” Howard said. Even though the neural mechanisms that allow us to remember an event like our first day of school are different than those that allow us to remember a fact like a phone number or a skill like how to ride a bike, they might rely on this common foundation.

The discovery of time cells in those brain regions (“When you go looking for them, you see them everywhere,” according to Howard) seems to support the idea. So have recent findings — soon to be published by Howard, Elizabeth Buffalo at the University of Washington and other collaborators — that monkeys viewing a series of images show the same kind of temporal activity in their entorhinal cortex that Tsao observed in rats. “It’s exactly what you’d expect: the time since the image was presented,” Howard said.

He suspects that record serves not just memory but cognition as a whole. The same mathematics, he proposes, can help us understand our sense of the future, too: It becomes a matter of translating the functions involved. And that might very well help us make sense of timekeeping as it’s involved in the prediction of events to come (something that itself is based on knowledge obtained from past experiences).

Howard has also started to show that the same equations that the brain could use to represent time could also be applied to space, numerosity (our sense of numbers) and decision-making based on collected evidence — really, to any variable that can be put into the language of these equations. “For me, what’s appealing is that you’ve sort of built a neural currency for thinking,” Howard said. “If you can write out the state of the brain … what tens of millions of neurons are doing … as equations and transformations of equations, that’s thinking.”

He and his colleagues have been working on extending the theory to other domains of cognition. One day, such cognitive models could even lead to a new kind of artificial intelligence built on a different mathematical foundation than that of today’s deep learning methods. Only last month, scientists built a novel neural network model of time perception, which was based solely on measuring and reacting to changes in a visual scene. (The approach, however, focused on the sensory input part of the picture: what was happening on the surface, and not deep down in the memory-related brain regions that Tsao and Howard study.)

But before any application to AI is possible, scientists need to ascertain how the brain itself is achieving this. Tsao acknowledges that there’s still a lot to figure out, including what drives the lateral entorhinal cortex to do what it’s doing and what specifically allows memories to get tagged. But Howard’s theories offer tangible predictions that could help researchers carve out new paths toward answers.

Of course, Howard’s model of how the brain represents time isn’t the only idea out there. Some researchers, for instance, posit chains of neurons, linked by synapses, that fire sequentially. Or it could turn out that a different kind of transform, and not the Laplace transform, is at play.

Those possibilities do not dampen Howard’s enthusiasm. “This could all still be wrong,” he said. “But we’re excited and working hard.”

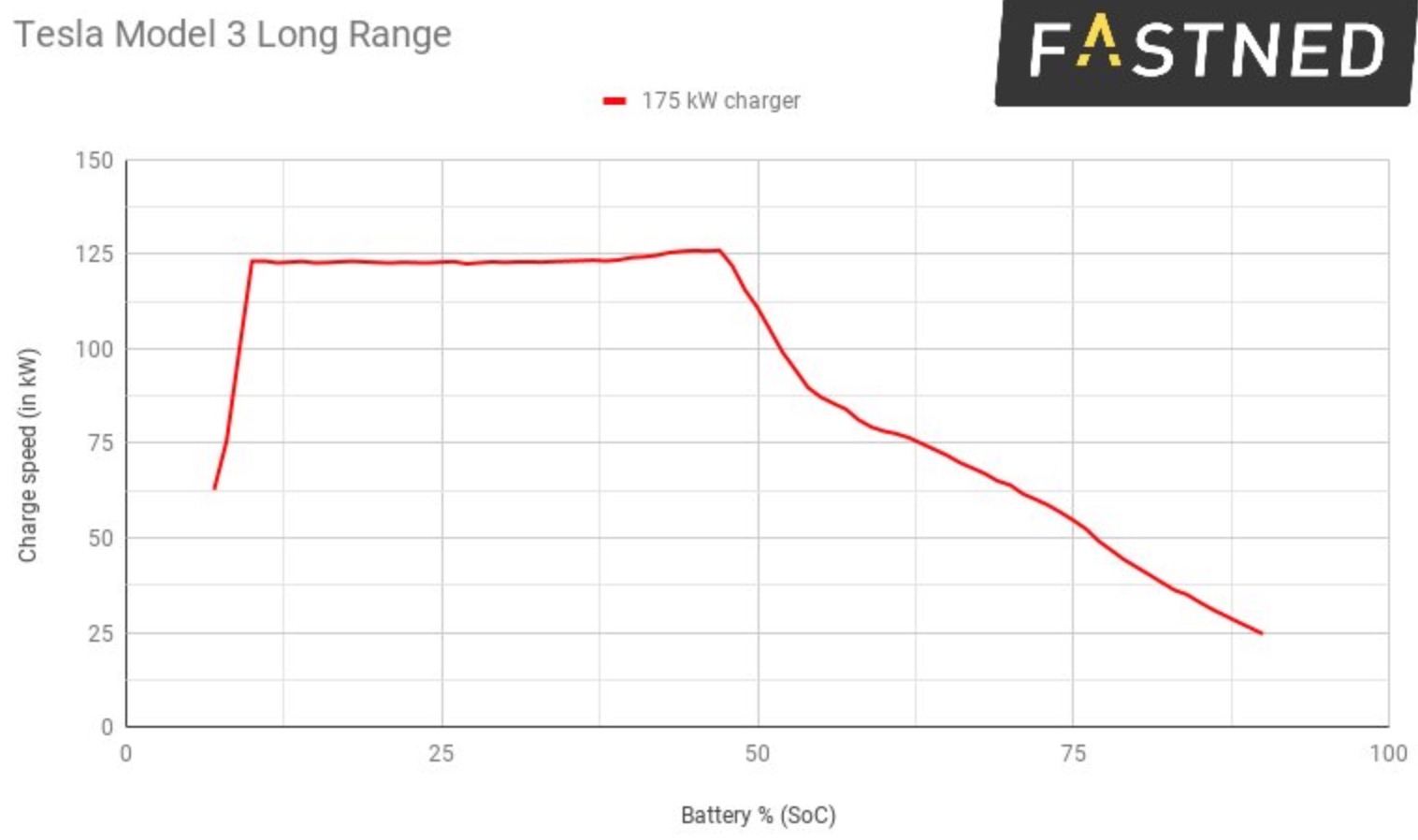

The first European production Tesla Model 3 stopped at a 175 kW CCS charging station and recorded a new charge rate record for the electric vehicle: 126 kW – 5 kW higher than on than on Tesla’s own Superchargers.

The first European production Tesla Model 3 stopped at a 175 kW CCS charging station and recorded a new charge rate record for the electric vehicle: 126 kW – 5 kW higher than on than on Tesla’s own Superchargers.

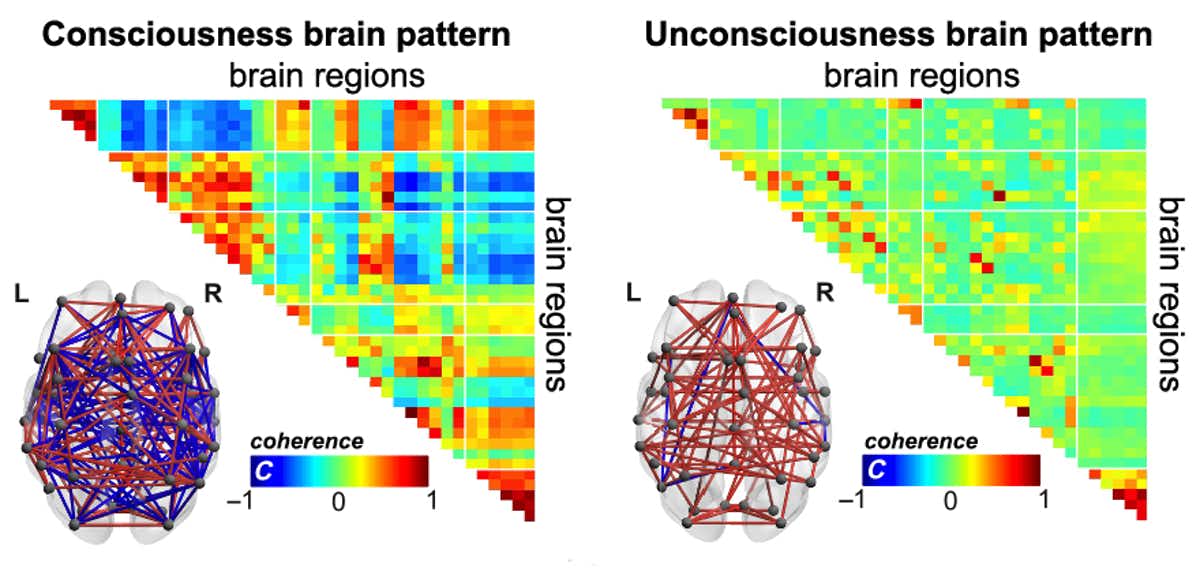

In fact, while scientists have been preoccupied with understanding consciousness for centuries, it remains one of the most important unanswered questions of modern neuroscience.

In fact, while scientists have been preoccupied with understanding consciousness for centuries, it remains one of the most important unanswered questions of modern neuroscience.

fMRI scanner (Semiconscious/Wikipedia/Public Domain)

fMRI scanner (Semiconscious/Wikipedia/Public Domain) (Tagliazucchi et al. 2019)

(Tagliazucchi et al. 2019)