It’s raining on your walk to the station after work, but you don’t have an umbrella. Out of the corner of your eye, you see a rain jacket in a shop window. You think to yourself: “A rain jacket like that would be perfect for weather like this.”

Later, as you’re scrolling on Instagram on the train, you see a similar-looking jacket. You take a closer look. Actually, it’s exactly the same one – and it’s a sponsored post. You feel a sudden wave of paranoia: did you say something out loud about the jacket? Had Instagram somehow read your mind?

While social media’s algorithms sometimes appear to “know” us in ways that can feel almost telepathic, ultimately their insights are the result of a triangulation of millions of recorded externalized online actions: clicks, searches, likes, conversations, purchases and so on. This is life under surveillance capitalism.

As powerful as the recommendation algorithms have become, we still assume that our innermost dialogue is internal unless otherwise disclosed. But recent advances in brain-computer interface (BCI) technology, which integrates cognitive activity with a computer, might challenge this.

In the past year, researchers have demonstrated that it is possible to translate directly from brain activity into synthetic speech or text by recording and decoding a person’s neural signals, using sophisticated AI algorithms.

While such technology offers a promising horizon for those suffering from neurological conditions that affect speech, this research is also being followed closely, and occasionally funded, by technology companies like Facebook. A shift to brain-computer interfaces, they propose, will offer a revolutionary way to communicate with our machines and each other, a direct line between mind and device.

But will the price we pay for these cognitive devices be an incursion into our last bastion of real privacy? Are we ready to surrender our cognitive liberty for more streamlined online services and better targeted ads?

•••

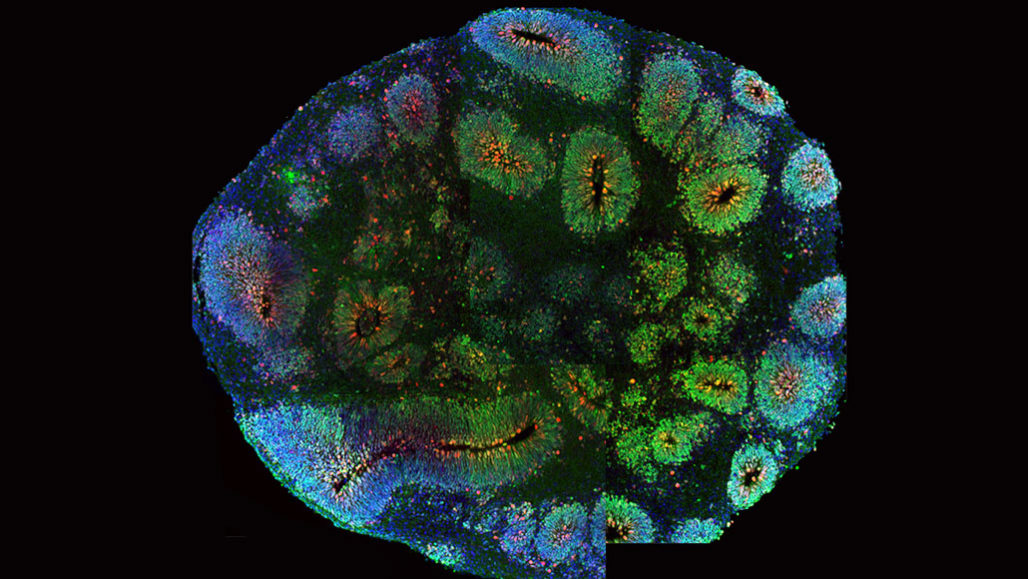

A BCI is a device that allows for direct communication between the brain and a machine. Foundational to this technology is the ability to decode neural signals that arise in the brain into commands that can be recognized by the machine.

Because neural signals in the brain are often noisy, decoding is extremely difficult. While the past two decades have seen some success decoding sensory-motor signals into computational commands – allowing for impressive feats like moving a cursor across a screen with the mind or manipulating a robotic arm – brain activity associated with other forms of cognition, like speech, have remained too complex to decode.

But advances in deep learning, an AI technique that mimics the brain’s ability to learn from experience, is changing what’s possible. In April this year, a research team at the University of California, San Francisco, published results of a successful attempt at translating neural activity into speech via a deep-learning powered BCI.

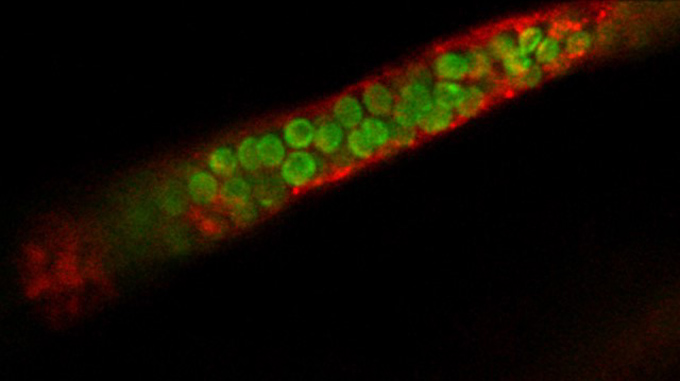

The team placed small electronic arrays directly on the brains of five people and recorded their brain activity, as well as the movement of their jaws, mouths and tongues as they read out loud from children’s books. This data was then used to train two algorithms: one learned how brain signals instructed the facial muscles to move; the other learned how these facial movements became audible speech.

Once the algorithms were trained, the participants were again asked to read out from the children’s books, this time merely miming the words. Using only data collected from neural activity, the algorithmic systems could decipher what was being said, and produce intelligible synthetic versions of the mimed sentences.

According to Gopala Anumanchipalli, a speech scientist who led the study, the results point a way forward for those suffering from “locked in” conditions, like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or brain stroke, where the patient is conscious but cannot voluntarily move the muscles that correspond to speech.

“At this stage we are using participants who can speak so this is only proof of concept,” he said. “But this could be transformative for people who have these neurological disabilities. It may be possible to restore their communication again.”

•••

But there are also potential applications for such technology beyond medicine. In 2017, Facebook announced that it would be investing in the development of non-invasive, wearable BCI that would allow Facebook users to “type with their brains”.

Since then, Facebook has funded research to achieve this goal, including a study by the same lab at University of California, San Francisco. In this study, participants listened to multiple-choice questions and responded aloud with answers while signals were being recorded directly from their brains, which served as input data to train decoding algorithms. After this, participants listened to more questions and again responded aloud, at which point the algorithms translated the one-word answers into text on a screen in real time.

While Facebook eagerly reported that these results indicated a step towards their goal of creating a device that will “let people type just by imagining the words they want to say”, according to Marc Slutzky, professor of neurology at Northwestern University, this technology is still a long way from what most people commonly understand as “mind-reading”.

State-of-the-art BCIs can only decode the neural signals associated with attempted speech, or the physical act of articulation, Slutzky told me. Decoding “imagined” speech, which is what Facebook ultimately wants to achieve, would require translating from abstract thoughts into language, which is a far more confounding problem.

“If someone imagines saying a sentence in their head but doesn’t at least attempt to physically articulate it, it is unclear how and where in the brain the imagined sentence is conceived,” he said.

Indeed, while many philosophers of language in the 20th century proposed that we think in sentence-like strings of language, use of brain imaging technology like electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocorticography (ECoG) has since revealed that thinking more probably happens in a complex combination of images and associations.

According to John Dylan Haynes, professor of neuroscience at the Charité Universitätsmedizin in Berlin, it is possible to decode and read out some of these signals to some degree, but this is still far off mind-reading. “That would require a full understanding of the language of the brain,” he said. “And to be very clear, we don’t fully understand the language of the brain.”

•••

But even if BCI technology can’t directly read minds doesn’t mean that a device couldn’t be used to reveal valuable and sensitive data about an individual. The structural brain scans recorded when someone is connected to a BCI, Haynes said, can reveal with reasonable accuracy whether someone is suffering from certain diseases or whether they have some other cognitive impairment.

While the management of this collateral data is heavily regulated in research institutes Haynes told me that no such regulations are in place for technology companies. Observing how some companies have, over the past decade, transformed troves of personal data into profit while displaying a wanton attitude to securing such data makes Haynes wary of the growing consumer BCI industry. “I’d be very careful about giving up our cognitive information to companies,” he said.

According to Marcello Ienca, a research fellow at ETH Zurich who evaluates the ethics of neuro-technology, the implications of private companies gaining access to cognitive data should be carefully considered.

“We have already reached a point where analysts at social media companies can use online data to make reliable guesses about pregnancy or suicidal ideation,” he said.

“Once consumer BCIs become widespread and we have enough brain recordings in the digital eco-system, this incursion into parts of ourselves that we thought were unknowable is going to be even more pronounced.”

For some, however, the development of BCI technology is not only about the potential consumer applications, but more profoundly about merging humans with machines. Elon Musk, for example, has said that the driving impetus in starting his own BCI company, Neuralink, which wants to weave the brain with computers using flexible wire threads, is to “achieve a symbiosis with artificial intelligence”.

Adina Roskies, professor of philosophy at Dartmouth University, says that while such a “cyborg future” might seem compelling, it raises thorny ethical questions around identity and moral responsibility. “When BCIs decode neural activity into some sort of action [like moving a robot arm] an algorithm is included in the cognitive process,” she explained. “As these systems become more complex and abstract, it might become unclear as to who the author of some action is, whether it is a person or machine.”

As Christian Herff, professor in the department of neurosurgery at Maastricht University explained to me, some of the systems currently capable of translating neural activity into speech incorporate techniques that are similar to predictive texting. After brain signals are recorded, a predictive system, not unlike those that power Siri and Alexa, tells the algorithm which words can be decoded and in what order they should go. For example, if the algorithm decodes the phrase “I is” the system might change that to “I am”, which is a far more likely output.

“In the case where people can’t articulate their own words, these systems will help produce some sort of verbalization that they presumably want to produce,” Roskies said. “But given what we know about predictive systems, you can at least imagine cases in which these things produce outputs that don’t directly reflect what the person intended.”

In other words, instead of reading our thoughts, these devices might actually do some of the thinking for us.

Roskies emphasized that we are still a fair way off such a reality, and that oftentimes, companies overhype technological ability for the sake of marketing hype. “But I do believe that the time to start thinking through some of the ethical implications of these systems is now,” she said.

Illustration: Mozilla

Illustration: Mozilla