Top 10 Fears that Hold People Back in Life

Acknowledging your fears and facing them head-on is key to reaching your goals.

Posted Jan 28, 2020

Whether your fears involve your relationship, career, death, or discomfort, staying inside your comfort zone will ensure you live a small life.

In fact, as a therapist, I see a lot of people work so hard to prevent themselves from ever feeling anxious that they actually develop depression. Their efforts to keep themselves comfortable inadvertently backfire. They live boring, safe lives that are void of the risk and excitement they need to feel fully alive.

Here are the top 10 fears that hold people back in life:

1. Change

We live in an ever-changing world, and change happens more rapidly than ever before. Despite this fact, however, there are many people who fear change, so they resist it.

This can cause you to miss out on many promising opportunities that come your way. You run the risk of being stagnant and staying stuck in a rut when you avoid change.

2. Loneliness

The fear of loneliness can sometimes cause people to resist living alone or even to stay in bad relationships. Or the fear of loneliness can cause people to obsessively use social media to the extent that they miss out on making face-to-face connections.

And while it’s smart to ward off loneliness (studies show it’s just as harmful to your health as smoking), it’s important to surround yourself with healthy people and healthy social interactions.

3. Failure

One of the most common fears on earth is the fear of failure. It’s embarrassing to fail. And it may reinforce your beliefs that you don’t measure up.

You also might avoid doing anything where success isn’t guaranteed. Ultimately, you’ll miss out on all the life lessons and opportunities that might help you find success.

4. Rejection

Many people avoid things like meeting new people or trying to enter into a new relationship because of the fear of rejection. Even individuals who are already married sometimes avoid asking their long-time spouse for something, imagining that the person will say no.

Whether you’re scared to ask that attractive person out on a date or to ask your boss for a raise, the fear of rejection could keep you stuck. And while rejection stings, it doesn’t hurt as much as a missed opportunity.

5. Uncertainty

People often avoid trying something different for fear of uncertainty. After all, there’s no guarantee that doing something new will make life better.

But staying the same is one surefire way to stay stagnant. Whether you’re afraid to accept a new job or afraid to move to a new city, don’t let the fear of uncertainty hold you back.

6. Something Bad Happening

It is an unfortunate and inevitable fact that bad things will happen in life. And sometimes, the fear of doom prevents people from enjoying life.

You can’t prevent bad things from happening all the time. But don’t let that fear stop you from living a rich, full life that’s also full of good things.

7. Getting Hurt

Hopefully, your parents or a trusted adult taught you to look both ways before you cross the street so that you won’t get hurt. But quite often, our fears of getting hurt cause us to become emotionally overprotective of ourselves.

Your fear of uncomfortable feelings and emotional wounds might prevent you from making deep, meaningful connections. Or it might stop you from being vulnerable at work. But without emotional risk, there aren’t any rewards.

8. Being Judged

It’s normal to want to be liked. But the fear of being judged can prevent you from being your true self.

The truth is, some people will judge you harshly no matter what. But trusting that you’re mentally strong enough to live according to your values is key to living your best life.

9. Inadequacy

Another fear shared by many people is the feeling of not being good enough. If you feel like you don’t measure up, you might become an underachiever. Or you might become a perfectionist in an effort to try and prove your worth.

The fear of inadequacy can be deep-rooted. And while it’s hard to face it head-on, you’ll never succeed until you feel worthy of your success.

10. Loss of Freedom

A certain amount of this fear can be healthy, but it becomes a problem when it holds you back in life. For many people, the fear of the loss of freedom becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

For example, someone who wants to live a free life might avoid getting a job with a steady income. Consequently, they might miss out on the freedom that comes with financial stability. So it’s important to consider what you’re giving up when you fear to lose certain freedoms.

Build Your Mental Muscle

Fortunately, you don’t have to let your fears keep you stuck. You can face your fears head-on, one small step at a time.

Facing your fears builds mental muscle. And the more mental muscle you have, the easier it is to face your fears.

So get proactive about doing the things that scare you and building the mental strength you need to live your best life.

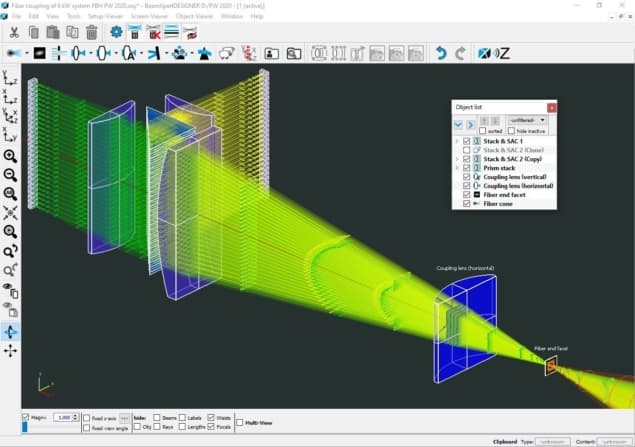

Scottish laser manufacturer

Scottish laser manufacturer

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66206800/steven-sinofsky-microsoft-stock_1020.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4252849/ipad1_2040.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2664256/DSC_1482-gal.1351039216.jpg)