Being ‘mind-blind’ may make remembering, dreaming and imagining harder

by University of New South Wales

Picture the sun setting over the ocean.

It’s large above the horizon, spreading an orange-pink glow across the sky. Seagulls are flying overhead and your toes are in the sand.

Many people will have been able to picture the sunset clearly and vividly—almost like seeing the real thing. For others, the image would have been vague and fleeting, but still there.

If your mind was completely blank and you couldn’t visualise anything at all, then you might be one of the 2-5 percent of people who have aphantasia, a condition that involves a lack of all mental visual imagery.

“Aphantasia challenges some of our most basic assumptions about the human mind,” says Mr Alexei Dawes, Ph.D. Candidate in the UNSW School of Psychology.

“Most of us assume visual imagery is something everyone has, something fundamental to the way we see and move through the world. But what does having a ‘blind mind’ mean for the mental journeys we take every day when we imagine, remember, feel and dream?”

Mr Dawes was the lead author on a new aphantasia study, published today in Scientific Reports. It surveyed over 250 people who self-identified as having aphantasia, making it one of the largest studies on aphantasia yet.

“We found that aphantasia isn’t just associated with absent visual imagery, but also with a widespread pattern of changes to other important cognitive processes,” he says.

“People with aphantasia reported a reduced ability to remember the past, imagine the future, and even dream.”

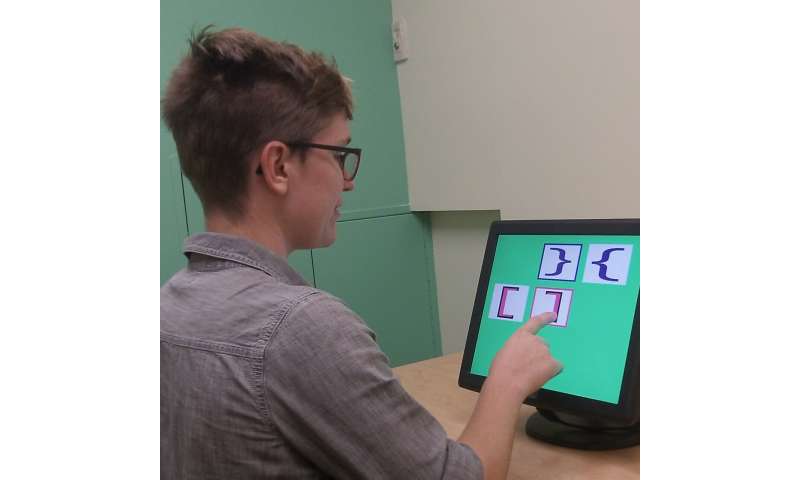

Study participants completed a series of questionnaires on topics like imagery strength and memory. The results were compared with responses from 400 people spread across two independent control groups.

For example, participants were asked to remember a scene from their life and rate the vividness using a five-point scale, with one indicating “No image at all, I only ‘know’ that I am recalling the memory,” and five indicating “Perfectly clear and as vivid as normal vision.”

“Our data revealed an extended cognitive ‘fingerprint’ of aphantasia characterised by changes to imagery, memory, and dreaming,” says Mr Dawes.

“We’re only just starting to learn how radically different the internal worlds of those without imagery are.”

Subsets of aphantasia

While people with aphantasia wouldn’t have been able to picture the image of the sunset mentioned above, many could have imagined the feeling of sand between their toes, or the sound of the seagulls and the waves crashing in.

However, 26 percent of aphantasic study participants reported a broader lack of multi-sensory imagery—including imagining sound, touch, motion, taste, smell and emotion.

“This is the first scientific data we have showing that potential subtypes of aphantasia exist,” says Professor Joel Pearson, senior author on the paper and Director of UNSW Science’s Future Minds Lab.

Interestingly, spatial imagery—the ability to imagine distance or locational relationship between things—was the only form of sensory imagery that had no significant changes across aphantasics and people who could visualise.

“The reported spatial abilities of aphantasics were on par with the control groups across many types of cognitive processes,” says Mr Dawes. “This included when imagining new scenes, during spatial memory or navigation, and even when dreaming.”

In action, spatial cognition could be playing Tetris and imagining how a certain shape would fit into the existing layout, or remembering how to navigate from A to B when driving.

In dreams and memories

While visualising a sunset is a voluntary action, involuntary forms of cognition—like dreaming—were also found to occur less in people with aphantasia.

“Aphantasics reported dreaming less often, and the dreams they do report seem to be less vivid and lower in sensory detail,” says Prof Pearson.

“This suggests that any cognitive function involving a sensory visual component—be it voluntary or involuntary—is likely to be reduced in aphantasia.”

Aphantasic individuals also experienced less vivid memories of their past and reported a significantly lower ability to remember past life events in general.

“Our work is the first to show that aphantasic individuals also show a reduced ability to remember the past and prospect into the future,” says Mr Dawes. “This suggests that visual imagery might play a key role in memory processes.”

Looking ahead

While up to one million Australians could have aphantasia, relatively little is known about it—to date, there have been less than 10 scientific studies on the condition.

More research is needed to deepen our understanding of aphantasia and how it impacts the daily lives of those who experience it.

“If you are one of the million Australians with aphantasia, what do you do when your yoga teacher asks you are asked to ‘visualise a white light’ during a meditation practice?” asks Mr Dawes.

“How do you reminisce on your last birthday, or imagine yourself relaxing on a tropical beach while you’re riding the train home? What’s it like to dream at night without mental images, and how do you ‘count’ sheep before you fall asleep?”

The researchers note that while this study is exciting for its scope and comparatively large sample size, it is based on participants’ self-reports, which are subjective by nature.

Next, they plan to build on the study by using measurements that can be tested objectively, like analysing and quantifying people’s memories.

Explore furtherAphantasia clears the way for a scientific career path

More information: Alexei J. Dawes et al. A cognitive profile of multi-sensory imagery, memory and dreaming in aphantasia, Scientific Reports (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-65705-7Journal information:Scientific ReportsProvided by University of New South Wales

Credit:

Credit:

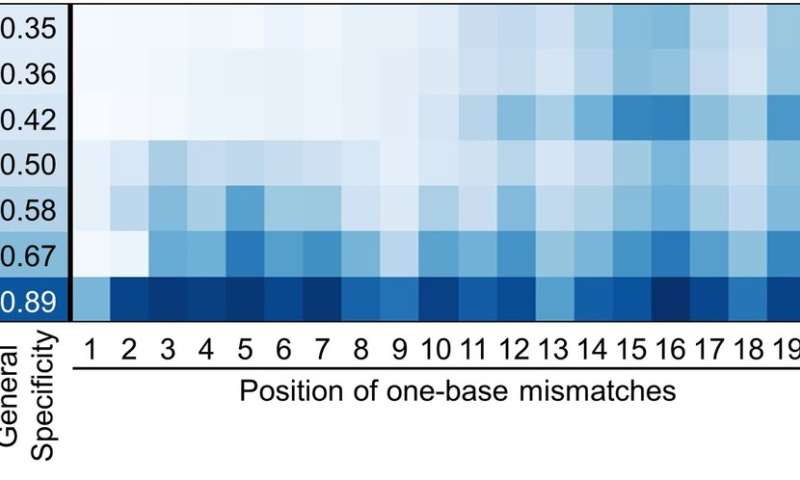

Figure 3. Comparing the specificity of the SpCas9 variants with a DNA sequence that has a single mismatch between the guide RNA and the target sequence. evoCas9 and the original SpCas9 exhibit the highest and the lowest specificity, respectively. Credit: Institute for Basic Science

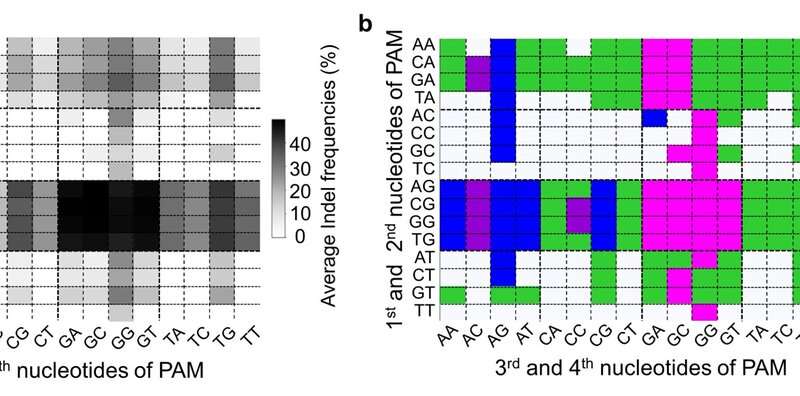

Figure 3. Comparing the specificity of the SpCas9 variants with a DNA sequence that has a single mismatch between the guide RNA and the target sequence. evoCas9 and the original SpCas9 exhibit the highest and the lowest specificity, respectively. Credit: Institute for Basic Science Figure 2. PAM compatibilities for SpCas9 variants. (a) Darker colors indicates higher frequency of DNA cleavage. (b) Among these four variants (SpCas9, VRQR, xCas9 and SpCas9-NG), SpCas9-NG has been the traditional choice for all PAM sequences that have a guanine (G) as the second nucleotide. However, these results shows that for PAM sequences AGAG and GGCG, for example, the Cas9 variant VRQR (in blue) would be preferable. Credit: Institute for Basic Science

Figure 2. PAM compatibilities for SpCas9 variants. (a) Darker colors indicates higher frequency of DNA cleavage. (b) Among these four variants (SpCas9, VRQR, xCas9 and SpCas9-NG), SpCas9-NG has been the traditional choice for all PAM sequences that have a guanine (G) as the second nucleotide. However, these results shows that for PAM sequences AGAG and GGCG, for example, the Cas9 variant VRQR (in blue) would be preferable. Credit: Institute for Basic Science Sipeed has launched a $72, open-spec “Sipeed TANG Hex” SBC that runs Linux on an FPGA-enabled Zynq-7020 with 1GB RAM, 256MB flash, 10/100 Ethernet, 4x USB 2.0 ports, and an early RPi-like 26-pin GPIO header.

Sipeed has launched a $72, open-spec “Sipeed TANG Hex” SBC that runs Linux on an FPGA-enabled Zynq-7020 with 1GB RAM, 256MB flash, 10/100 Ethernet, 4x USB 2.0 ports, and an early RPi-like 26-pin GPIO header.