Researchers Discover How the Brain Paralyzes You While You Sleep

TOPICS:NeurosciencePhysiologySleep ScienceUniversity Of Tsukuba

By UNIVERSITY OF TSUKUBA JANUARY 17, 2021

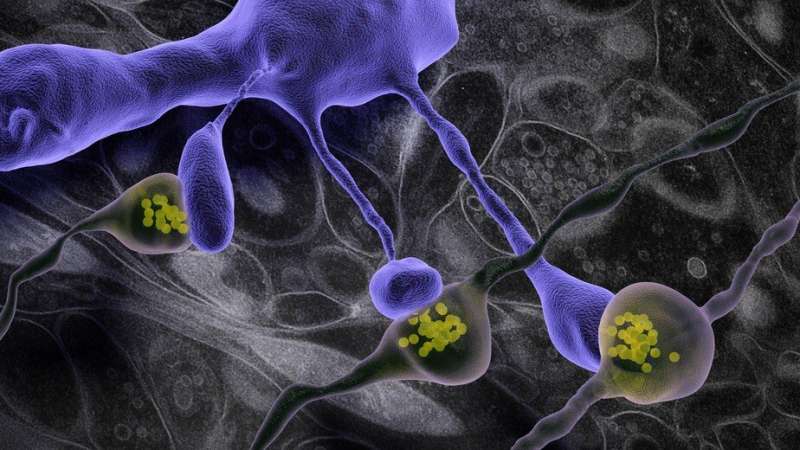

Researchers at the University of Tsukuba in Japan have discovered a group of neurons in the mouse brainstem that suppress unwanted movement during rapid eye movement sleep.

We laugh when we see Homer Simpson falling asleep while driving, while in church, and while even operating the nuclear reactor. In reality though, narcolepsy, cataplexy, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder are all serious sleep-related illnesses. Researchers at the University of Tsukuba led by Professor Takeshi Sakurai have found neurons in the brain that link all three disorders and could provide a target for treatments.

REM sleep correlates when we dream. Our eyes move back and forth, but our bodies remain still. This near-paralysis of muscles while dreaming is called REM-atonia, and is lacking in people with REM sleep behavior disorder. Instead of being still during REM sleep, muscles move around, often going as far as to stand up and jump, yell, or punch. Sakurai and his team set out to find the neurons in the brain that normally prevent this type of behavior during REM sleep.

Working with mice, the team identified a specific group of neurons as likely candidates. These cells were located in an area of the brain called the ventral medial medulla and received input from another area called the sublaterodorsal tegmental nucleus, or SLD. “The anatomy of the neurons we found matched what we know,” explains Sakurai. “They were connected to neurons that control voluntary movements, but not those that control muscles in the eyes or internal organs. Importantly, they were inhibitory, meaning that they can prevent muscle movement when active.” When the researchers blocked the input to these neurons, the mice began moving during their sleep, just like someone with REM sleep behavior disorder.

Narcolepsy, as demonstrated by Homer Simpson, is characterized by suddenly falling asleep at any time during the day, even in mid-sentence (he was diagnosed with narcolepsy). Cataplexy is a related illness in which people suddenly lose muscle tone and collapse. Although they are awake, their muscles act as if they are in REM sleep. Sakurai and his team suspected that the special neurons they found were related to these two disorders. They tested their hypothesis using a mouse model of narcolepsy in which cataplexic attacks could be triggered by chocolate. “We found that silencing the SLD-to-ventral medial medulla reduced the number of cataplexic bouts,” says Sakurai.

Overall, the experiments showed these special circuits control muscle atonia in both REM sleep and cataplexy. “The glycinergic neurons we have identified in the ventral medial medulla could be a good target for drug therapies for people with narcolepsy, cataplexy, or REM sleep behavior disorder”, says Sakurai. “Future studies will have to examine how emotions, which are known to trigger cataplexy, can affect these neurons.”

Reference: “A discrete glycinergic neuronal population in the ventromedial medulla that induces muscle atonia during REM sleep and cataplexy in mice” by Shuntaro Uchida, Shingo Soya, Yuki C. Saito, Arisa Hirano, Keisuke Koga, Makoto Tsuda, Manabu Abe, Kenji Sakimura and Takeshi Sakurai, 28 December 2020, Journal of Neuroscience.

DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0688-20.2020

We recommend

- “Just Go To Sleep!” Sleep & LearningJenny L. Williamson et al., The American Biology Teacher, 2014

- A systems approach to self‐organization in the dreaming brainStanley Krippner et al., Kybernetes, 2002

- A case of attempted bilateral self-enucleation in a patient with bipolar disorderHannah Muniz Castro et al., Mental Illness, 2017

- Management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in Canada during the coronavirus pandemicL.H. Sehn et al., Current Oncology, 2020

- Electromyography features during physical and imagined standing up in healthy young adultsKanokwan Srisupornkornkool et al., Journal of Health Research, 2020